Isaac Newton and Bernardine Hagan House | |

| |

| |

| Location | 723 Kentuck Road, Chalkhill, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Uniontown, Pennsylvania |

| Coordinates | 39°52′9″N 79°31′11″W / 39.86917°N 79.51972°W |

| Built | 1953–56 |

| Architect | Frank Lloyd Wright |

| Architectural style | Usonian |

| NRHP reference No. | 00000708[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | May 16, 2000[1] |

| Designated NHL | May 16, 2000[2] |

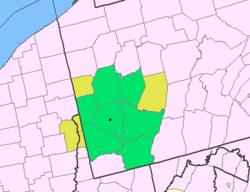

Kentuck Knob (also known as the Hagan House) is a house in Stewart Township, near the village of Chalkhill, in Fayette County, Pennsylvania, United States. Designed by the architect Frank Lloyd Wright in the Usonian style, the residence was developed for I. N. Hagan, the owner of a local ice-cream firm, along with his wife Bernardine. it is built on the southern slope of a knoll known as Kentuck Knob, overlooking the Youghiogheny River gorge. The name of the house and knoll is derived from an 18th-century settler who was planning to move to Kentucky. The house is designated as a National Historic Landmark.

I. N. and Bernardine Hagan had learned of Wright's work through Edgar J. Kaufmann, a businessman who had hired Wright to design the Fallingwater house in Fayette County. The Hagans purchased 79 acres (32 ha) of land near Uniontown, Pennsylvania, in July 1953 and asked Wright to design them a Usonian home for them. Despite being busy with multiple other projects, Wright agreed to design a house at Kentuck Knob, which was completed in 1956. The Hagans lived at Kentuck Knob until 1986, when they sold the property to Peter Palumbo, Baron Palumbo. The house was damaged by a fire shortly afterward, and the Palumbo family renovated the house afterward. Kentuck Knob has been open to the public for tours since 1996, and a visitor center there was completed in 2003.

The estate, accessed by a driveway from Pennsylvania State Route 2010, includes approximately 8,800 trees and a sculpture garden for the Palumbo family's art collection. The house itself is made of redwood and locally-quarried stone, with an overhanging copper roof and two exterior terraces. It is laid out around a hexagonal floor plan, which consists of two wings that partially surround a courtyard, converging at a hexagonal core. The interior covers 2,300 square feet (210 m2) and consists of seven rooms in an open plan arrangement. The kitchen, within the house's core, is surrounded by a living room to the west and a dining room to the west. Extending northeast of the core are three bedrooms, which are partially embedded into the hillside. The house's carport, which includes an art studio, is attached to the bedroom wing.

Site

[edit]Kentuck Knob is situated in Stewart Township, near the village of Chalkhill, in the Laurel Highlands of Fayette County in southwestern Pennsylvania, United States.[3][4] It is located approximately 70 miles (110 km) southeast of Pittsburgh.[5] The estate was originally owned by the Hagan family and spanned 79 acres (32 ha);[3][6][a] it has been expanded over the years to more than 600 acres (240 ha).[8] The estate is next to the Youghiogheny River,[4][9] although the river gorge is not readily visible from the house due to the presence of trees.[10][11] The building itself is on the southern slope of a hill also known as Kentuck Knob, the peak of which is variously cited as measuring 2,050 feet (620 m)[3][12] or 2,080 feet (630 m) high.[13][14]

Geography and site usage

[edit]The house is accessed via a 1⁄4-mile (0.40 km) gravel driveway leading from Pennsylvania Route 2010 (PA 2010),[3] which winds through some woods and passes above a waterfall called Cucumber Falls.[13] In addition to the main house, the property includes a greenhouse, farmhouse, barn, and wooden sheds;[3][15] the greenhouse was salvaged from the nearby Fallingwater.[16][17][18] The site had originally been farmland, but after the Hagans acquired it, they planted about 8,800 trees on the hill.[3][17][19] The driveway is illuminated by a copper lamppost designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, who also designed the house.[20]

After the family of Peter Palumbo, Baron Palumbo, acquired the house, they added a sculpture meadow,[4] which is accessed by a winding trail that connects to the visitor center.[6][20] The meadow includes works by artists such as Harry Bertoia, Scott Burton, Anthony Caro, Andy Goldsworthy, Alvar Gullichsen, Allen Jones, Phillip King, David Nash, Claes Oldenburg, Eva Reichl, George Rickey, Ray Smith, Wendy Taylor, and Michael Warren.[20] Other pieces in the sculpture garden include two graffitied pieces of the Berlin Wall,[21] a restroom structure, English telephone kiosks, and a pissoir.[20][22] The sculptures are generally made of materials like granite, steel, and wood, complementing the design of the main house.[23]

Surroundings

[edit]The Sugarloaf Knob mountain is southeast of the house, while the Fort Necessity National Battlefield is to the southwest.[24] In addition, a conservation easement for Ohiopyle State Park abuts the estate.[25] Kentuck Knob is one of four buildings in southwestern Pennsylvania designed by Wright. The others are Fallingwater about 7 miles (11 km) to the northeast,[26][27] as well as Duncan House[27][28] and Lindholm House at Polymath Park in Acme, Pennsylvania.[29] Aside from Fallingwater, Kentuck Knob is the only other house in Fayette County that Wright designed.[30]

The name originates from David Askins, a settler who wanted to move to Kentucky in the late 18th century before moving to a hill in Fayette County, which he called Little Kentuck.[3][31] The Askins site, formed through the merger of the Mitchell, Morris, and Thorpe families' farms,[31] later became Stewart Township's Kentuck District.[3] Because the area is mountainous, it has remained largely undeveloped over the years.[3][32]

History

[edit]Development

[edit]The Kentuck Knob house was developed for the Hagan family, which owned a major dairy company in Western Pennsylvania (Hagan Ice Cream, later acquired by Crowley Foods).[33] The family then lived in an undistinguished brick house in Uniontown, Pennsylvania; they collected textiles and pottery, which did not fit the style of their Uniontown house.[34] Isaac Newton "I. N." Hagan and his wife Bernadette were acquainted with the family of Edgar J. Kaufmann, who built the nearby Fallingwater in the late 1930s.[6][13] Kaufmann had first met I. N. Hagan several years before Kentuck Knob's construction, when he asked Hagan about whether he could bottle local farmers' milk.[35][36] The Hagans learned about Wright's work through the Kaufmanns, whom they sometimes visited.[34][37] After multiple trips to Fallingwater, Bernardine came to regard it as "a very beautiful, unusual place",[34][37] while I. N. said that he had become more attracted to Fallingwater on each successive visit.[37][22] As I. N. later said, "My wife and I have always had our hearts set on living on a Wright home."[38] Their son Paul, an aspiring architect, had also taken an interest in Fallingwater's design.[37][39]

Design

[edit]

The Hagans bought a 79-acre tract in the mountains south of Uniontown in July 1953,[39][40] where they wanted Wright to design a house.[6][36] I. N. reached out to Kaufmann, who advised the Hagans to call Wright, not write to him, about whether he would design them a house.[37][39] Though the tract was remote, the growing popularity of the automobile meant that they could easily drive to Uniontown.[39][41] In August 1953, the Hagans brought Paul and his friend James Baker to Fallingwater just before Paul's wedding. The same day, I. N. wrote to Wright, asking the architect to design them a home.[36] Wright took his time responding, even though, according to the scholar Donald Hoffmann, the Hagans' mountainside site "should have immediately appealed to him".[41] The Hagans called Wright, who invited them to Taliesin, his studio in Wisconsin.[42]

Later that August, the Hagans traveled to Wright's studio.[39][43] The family requested that Wright design a one-story stone-and-wood structure with three bedrooms and two bathrooms,[39] and Wright claimed he could "shake a design out of my sleeve".[44] To determine how the house should be designed, Wright asked about their hobbies and what they wanted in a house.[45] He also asked the Hagans if they were "nesters or perchers" to determine whether to design the house beside the hill or atop it.[12] Wright decided to build the house on the southern slope of the hill, instead of on its summit.[40] When the family returned to Pennsylvania, they toured the Richard C. Smith House, Unitarian Meeting House, and Jacobs First House, all designed by Wright.[39][43] The buildings influenced the final design of Kentuck Knob; the Smith House and Meeting House were both arranged on a grid with 60-degree angles, and the Hagans liked the Meeting House's copper roof and the Smith House's dentils and trellises.[39][46] The Hagans also traveled to New York City to see an exhibit about a Usonian house.[47][48] I. N. wrote back to Wright in September 1953 to tell him about the site, saying that the peak of the knoll "probably presents a pretty discouraging picture".[24]

John H. Howe, Wright's chief draftsman and longtime apprentice, drew up the plans for the house.[49][50][51] Because Howe did not visit the actual site, the early drawings were riddled with errors.[50] Wright also did not visit the site until the design was completed,[7][16] instead relying on contour maps.[16][46] The initial plans were completed by February 1954;[52] the design included a drawing of the site with random boulders scattered throughout.[7] Though Wright was known to be irascible and resistant to change, he readily modified the design based on the Hagans' requests.[11][38] For instance, he lengthened the living room and added a painting studio for Bernadette.[52] Wright modified the kitchen's floors and countertops and added a screen to the kitchen,[19][52] and he expanded the dining room upon learning that the Hagans did not frequently eat out.[53] He overruled some of the Hagans' other requests, such as a wider terrace[54] and a wider hallway.[55] The Hagans ultimately traveled to Taliesin and Wright's other studio, Taliesin West, five times to negotiate elements of the design.[19]

Construction

[edit]Work began in mid-1954.[52] At the time, Wright was either 86[56] or 87 years old,[57] yet he was still busy with the design of structures such as the Guggenheim Museum in New York, the Beth Sholom Synagogue in the Delaware Valley, and the Price Tower in Oklahoma.[45][50] The Hagans intended to spend $60,000 on the house.[46][58][59] Because Wright was known to exceed clients' budgets,[60][58] Kaufmann had advised the Hagans to tell Wright half the amount that they wanted to spend.[37][58] The Hagan family originally wanted to use Pottsville sandstone from the same quarry that provided Fallingwater's stone, but they instead decided to use stone from their own property.[61][57] Sources disagree on whether the Hagans rejected the Pottsville sandstone as too expensive[57] or whether they liked their own estate's stone more.[61]

By May 1954, the house was expected to cost more than twice its original estimate, $124,000, in part due to its secluded site.[59] The family hired local workers including the stonemason Jesse Wilson Sr. and the general contractor Herman Keys.[52][57] Wilson and his son Jesse Jr. began working on the stone in September 1954, training a small group of workers to split the stone.[57] One story has it that the stonemasons interpreted Wright's plans literally and found stones that were the same shape, and in the same locations as those that Wright had sketched out.[7][62] Wright visited the site once, spending three hours there during its construction.[28] During the visit, he expressed satisfaction with the stonemasons' work,[45] and he relocated the house's site by 10 feet (3.0 m) while keeping the plans otherwise unchanged.[16] Although the Friends of Fallingwater Newsletter wrote that Wright declined to assign an apprentice to oversee the project,[45] Wilson said that one of Wright's assistants directed him to make a sample wall section, then left once he was satisfied with the results.[57] Keys, meanwhile, convinced Wright to add reinforcement to the roof.[19]

The cement work and the bases of each wall were completed by early 1955, at which point the Wilsons began laying the stone. The construction supervisor largely let the Wilsons alone because he was unfamiliar with the masonry-laying process.[57] Two artisans were responsible for carving all the house's woodwork.[63] The house ultimately cost $82,329;[59] if furnishings are included, the total cost amounted to about $96,000[58][64] or $98,057.[50] In addition to the furniture that Wright designed for Kentuck Knob, the Hagan family acquired other furniture.[14][10] For example, the Kaufmanns' son Edgar Kaufmann Jr. took the Hagans to New York to buy Scandinavian furniture, and they hired George Nakashima to design additional pieces of furniture for the house.[10][65]

Hagan ownership

[edit]

The Hagans occupied the house in July 1956,[38][66] on their anniversary.[10][19] Passersby quickly began taking notice of the building,[66] and the Hagans sometimes came home to see sightseers gawking at it.[38][17] Visitors peered through the windows when the Hagans were absent, and they sometimes asked for tours when the Hagans were present.[67] The Hagans only sporadically allowed photographs and tours,[7] and the exact location of Kentuck Knob was originally not publicized because Bernardine Hagan wanted to "keep it as quiet as we could".[14] The house garnered less attention than the nearby Fallingwater, which later became a world-famous tourist attraction.[15][17] Despite the publicity, I. N. said that the house's beauty more than made up for the "occasional inconveniences".[38] Wright never visited the completed house prior to his death in 1959, saying that he already knew the house's appearance because he had designed it.[54] Wright also designed a building for Hagan Ice Cream, although this structure was not constructed.[51]

In the years after the Hagans moved in, they made several modifications to the estate.[65] For example, they planted thousands of tree seedlings outside the house,[17][19] and Bernadette modified the landscape by adding earthen terraces and a pathway.[65] The Hagans also added a small water fountain near the master bedroom,[63][65] and they acquired a greenhouse from Fallingwater.[18] Over the years, I. N. and Bernadette decorated the house with objects that they had acquired during their travels abroad, including two Thai prints.[68] By the early 1980s, the Hagans wanted to sell Kentuck Knob,[17] as I. N. had Alzheimer's disease, and Bernadette was worried that he would wander the estate and get lost.[19] In 1983, Sotheby's Parke-Bernet began advertising Kentuck Knob for sale on behalf of the Hagan family, with an asking price of $675,000.[14][15][69] This was the first time in the house's history that it had been placed for sale.[15] Because Kentuck Knob was so remote, the house remained unsold for several years.[22][70]

Palumbo ownership

[edit]Purchase

[edit]Lord Peter Palumbo learned of the house in April 1985 after visiting Fallingwater; upon learning about Kentuck Knob during that visit, Palumbo traveled there as well.[16] The Hartford Courant writes that Palumbo had learned about the house after overhearing someone else's conversation at Fallingwater,[71] while other sources wrote that someone told him about Kentuck Knob directly.[44][70][72] Lord Palumbo later said that he "fell in love with the outside" of Kentuck Knob and wanted to see the inside so urgently that he decided to purchase it;[12] he also described the site as being of "spectacular beauty" regardless of the season.[17] Palumbo decided to buy the house in 1986,[21][73] paying $600,000 for the property.[74][44] The Penobscot Corporation was recorded as the legal buyer;[75][76] the acquisition included not only the 79-acre Hagan estate but also 1,000 acres (400 ha) of woods around it.[77] At the time, Palumbo owned several other structures, including the Farnsworth House in Illinois and Jamoul in Paris.[12][73][78]

Shortly after the Palumbo family obtained the house, it was substantially damaged in a fire on May 26, 1986,[79] after a gardener put away a hot lawnmower that subsequently threw out sparks.[44] The blaze destroyed parts of the roof and caused smoke and water damage throughout the house,[76][79] which was vacant at the time.[75][76] After the fire, the Palumbo family renovated the interior, including the tidewater-cypress surfaces, and furnished the house with rare furnishings.[16][77] Robert Taylor, who had helped design the house, was hired to design its renovation as well.[44] Lord Palumbo added furniture by designers such as Frank Lloyd Wright, Carlo Bugatti, Charles Rennie Mackintosh, and Gustav Stickley.[4] In addition, he decorated the estate with several pieces of modern sculpture.[3][4] By the mid-1990s, the Palumbo family were often absent from the house for long periods,[77] and they alternated between their various houses to reduce wear and tear at Kentuck Knob.[62]

Opening as visitor attraction

[edit]

The family announced in March 1996 that it would open the house to tourists,[5][77] and public tours began that May.[11][78] At the time, Palumbo did not know if his adult children were interested in it, and he wanted to preserve the house as a cultural resource.[70][78] Kentuck Knob's visitor center was initially located within the estate's greenhouse,[80][73] and the estate's administrator Susan Waggoner trained 10 docents to give tours.[73] The various rooms were decorated with the Palumbo family's belongings,[6][11][62] in a similar fashion to English manors, whose owners often opened their houses to the public while continuing to live there.[81] Lord Palumbo and his wife continued to drop by on occasion,[6][78] but they typically left the house before 9 a.m., when visitors came in.[81] The tours typically were limited to either 8[73] or 15 people per group.[6] On occasion, the family joined the tours of their own house,[53][81] and Bernadette Hagan also visited her old residence sporadically.[19] The house was closed to visitors three weeks of the year, when the Palumbos resided there,[70] and it was also shuttered on Mondays.[22]

Within six months of opening to the public, Kentuck Knob had accommodated 13,000 visitors. In the long run, the Palumbo family wanted the house to be financially self-sufficient.[81] The family also continued to add artwork to the grounds; for example, they acquired Ray Smith's artwork Red Army in 1997,[82] and they obtained a George Rickey sculpture.[83] In addition, Palumbo bought extra land to give his family privacy,[84] and the house also began hosting limited tours during sunrise in the late 1990s.[85] Lord Palumbo also considered hiring Frank Gehry to design a permanent visitor center for Kentuck Knob, in addition to a master plan for the entire estate.[83] Palumbo decided against hiring Gehry after learning that the architect would charge $3 million for his design.[80] Afterward, Palumbo bought 22 acres (8.9 ha) next to the existing estate and hired Arthur Lubetz in May 2000 to design the visitor center for about $350,000.[80][86] The visitor center began construction that November and was financed by the Progress Fund.[87] The estate had accommodated more than 100,000 visitors by late 2000,[87] and the visitor center was completed in May 2003.[88]

In celebration of the house's 50th anniversary in 2006, three trees were dedicated on the grounds to honor the craftsmen that had helped erect the structure.[17] The house continues to operate as a tourist attraction in the 2020s. The Palumbos no longer lived there (instead residing in a farmhouse nearby), but they continued to own Kentuck Knob and were involved in the house's operation.[44] Tickets to the house include a tour of the house's interior and a walk around the estate;[20] the house tour is led by a docent, while the tour of the grounds is self-guided.[77] It is typically open to visitors between March and September of each year.[44]

Architecture

[edit]

Kentuck Knob is a single-story dwelling with three bedrooms.[71][89] The building is one of Wright's few remaining higher-end Usonian houses,[22] as well as an example of Wright's later Usonian work.[40] The house has two wings (a living-room wing and bedroom wing), which bend away from each other at a 120-degree angle[51][90] and are of equal length.[30][38] The wings converge at a hexagonal core,[11][78] which resembles a stone chimney.[91] The building's floor grid is based on a series of equilateral triangles,[50] which measure 4.5 feet (1.4 m) long on each side.[51][92][b] Most of the floor tiles are hexagonal,[11][71] though there are standalone triangles between each of the hexagons, which create overlapping hexagrams and parallelograms.[50] The house is variously cited as containing either 53,[16] 54,[44] or 58 exterior angles.[19][58][71] Due to the grid, the house is sometimes described as not having any right angles[15][71] or having only two right angles.[74][93] Vertically, the house is divided into courses measuring 13 inches (330 mm) high.[51]

The design includes elements of organic architecture.[38][70][94] For example, most of the stone for the house came from the estate itself,[7][66][92] though the floors use stone from Maryland.[51] Around 800 short tons (710 long tons; 730 t) of stone may have been used at Kentuck Knob.[22][57] The house also has woodwork made of Tidewater red cypress,[13][38] which was selected because the material did not rot easily; sources disagree on whether the wood came from Florida[38] or South Carolina.[7] Large amounts of glass are also used for the walls and rooftop skylights.[44] In a similar manner to a passive solar house,[10] the building is oriented to the west and south, since the house primarily received natural light from these directions throughout the year.[52] This orientation also allowed the living room to receive direct sunlight in the winter, but not in the summer.[51] The bedroom wing, extending to the northeast, is partly embedded into the adjacent knoll.[15][38][95] Kentuck Knob also includes typical Usonian features such as built-in furniture, narrow corridors, and a carport.[22]

Exterior

[edit]Courtyard and terraces

[edit]The wings surround a gravel courtyard, which faces west[90] and is accessed by the house's driveway.[13] There is a studio and a carport with a flat canopy on the eastern side of the courtyard, embedded into the knoll. In addition, a retaining wall runs along the courtyard's western border; the end of the retaining wall contains a stone planter with a copper lamp and a pyramidal shade.[90] There are also two large terraces just outside the house. The main terrace, the larger of the two, adjoins the living-room wing and extends west and south to the ramparts.[92] This terrace has a flagstone pavement[92] and extends the house's width.[70] Another flagstone terrace is located just outside the intersection of the two wings, to the southeast. The secondary terrace is surrounded by a retaining wall and includes a fountain to its north.[96] Both terraces are separated from the interior by glass walls to give the impression that the terraces are part of the interior space.[16]

Facade

[edit]The house sits on concrete ramparts with stone cladding, which measure 10 inches (250 mm) thick.[92] The sandstone facade is arranged in irregular horizontal courses[92] and is characterized as having a golden-brown tint.[13] When the house was built, Wright specified that the facade be composed of a pattern of two narrow courses between wider courses. Each of the walls is 12 inches (300 mm) thick, consisting of a 2-inch-thick (5.1 cm) insulating layer sandwiched between two layers of rock.[57] The walls are placed atop a concrete foundation.[52][57] To make the stonework appear more natural, the stone is laid irregularly, with random stones protruding past the rest of the facade.[52][40]

The main entrance is located within the house's core, where the wings intersect.[97][98] A flagstone stoop ascends to a set of double doors, where there are a small canopy and glass panels protruding from the facade.[98] Also on the facade, next to the entrance, is a small red tile where Wright inscribed his initials;[6][98] this makes Kentuck Knob one of 19 buildings where Wright signed his name.[20] A walkway with a flagstone pavement leads to the carport.[98]

The facade itself is lit indirectly by recessed triangular light bulbs[7][92] and is decorated with various geometric motifs.[99] On the southern, western, and eastern elevations are doors reaching from floor to ceiling, as well as wood-framed casement windows, all of which contain plate-glass panes.[90] The edges of one of the living-room windows are recessed within the stone wall, making it nearly imperceptible.[7][78] The northern elevation has small clerestories and deep eaves (or outward extensions of the roof) for privacy. The clerestories, near the tops of the facade, are composed of horizontal wooden cypress boards with cutouts.[78]

Roof

[edit]

The roof is mostly clad in copper,[51][71] and there are horizontal battens along the roof.[92] The roof was originally brown-colored but has oxidized into a blue-green color over the years.[14][68] A skylight and the house's primary chimney are located above the core, while another chimney is located in the northern (bedroom) wing, near the carport. The canopy of the carport, as well as the roof of the studio adjacent to it, have flat gravel roofs with copper drains.[92] The house has cantilevered eaves with hexagonal cutouts;[38][90][99] there are 24 hexagonal cutouts on the southern elevation alone.[7] On the entirety of the southern and western elevations, and part of the eastern elevation, the eaves range from 3 to 10 feet (0.91 to 3.05 m) long and are decorated with wooden dentils.[90] The eaves also contain triangular lights and downspouts.[7]

Interior

[edit]The house has seven rooms.[7] Its precise floor area is difficult to calculate because of its angled floor plan,[7] though it is commonly cited as having a floor area of 2,300 square feet (210 m2).[22][57][9][c] The kitchen occupies the center of the house, within the chimney core.[10][51] The living and dining rooms respectively extend west and south of the core, within the house's western wing, while the bedrooms extend northeast of the core, within the house's northern wing.[51][89] The house's soffits ascend toward a ridge, which measures 11 feet (3.4 m) high[99] and was intended to draw viewers' attention both to the center of the room and the landscape outside.[98] Other parts of the interior have low ceilings and narrow passageways.[94][99] The house has an open plan with few interior doors; instead, the orientation of the house itself was intended to provide privacy.[70]

The floors are mostly made of stone,[11][98][99] except for the carpeted living room and a cork floor in the kitchen.[11] The original plan called for a painted concrete surface, but the Hagans wanted a stone floor similar to Fallingwater's.[52] The walls and ceilings use glass, wood, and stone,[70] and the hardware throughout the house is made of brass.[98] In addition, there is a radiant heating system embedded into the floor.[6][92] Wright designed Kentuck Knob's built-in furniture,[7][98] which is made of red tidewater cypress and was built to fit the dimensions of the house.[98] There are also standalone furnishings designed by other decorators, including chairs by Hans Wegner, Finn Juhl, and George Nakashima,[19][65] as well as a chest and two tables designed by Nakashima.[10][19] Wright's associate Eugene Masselink designed a screen for the house as well.[18][51]

Living-room wing

[edit]

The main entrance opens into a foyer, which adjoins a kitchen within the house's core.[98] To the right (west) of the main entrance is the living room, which has a fireplace next to the house's central core.[98][95] The living room has a sofa measuring 28 feet (8.5 m) wide,[71][98] which faces south toward a group of glazed doors facing the terrace.[89] Much of the living room's floor is covered with a Moroccan carpet that was added after a fire in 1986. The sofa has movable cushions, which conceal storage space; there are cantilevered storage shelves and clerestory windows above the sofa. Throughout the living room are cabinets for electronics such as a record player, radio, and television, and there are additional cabinets on the south wall.[89] There is also a planter straddling the southern facade.[89][93] Along the core's west wall, on the eastern wall of the living room, is a chimney with a cantilevered fireplace lintel.[89] Electrical outlets are built into the living room's floor because Bernadette did not want their appearance to detract from the walls' design.[7] There is also fretwork that resembles the shapes of mountain ranges.[100]

The kitchen is hexagonal and measures around 15 feet (4.6 m) high.[84][99][101] with a domed skylight made of plexiglass,[38][101] Besides the skylight, the kitchen has no windows.[98][95] The room has a cork floor, stainless-steel countertops and sink, and cypress cabinets,[101] in addition to four stove burners that can be flipped down.[84][102] There is a dining room to the south of the kitchen and east of the living room, which also faces the terrace to the south.[89][95] The dining room's ceiling has hexagonal skylights, which are the same size as the horizontal cutouts in the eaves. The eastern wall of the dining room has a sideboard, while the window in the southwestern corner has miters.[101] The dining-room table is angled to fit within the hexagonal and triangular grid.[95][101] The ceiling above the dining room measures 6 feet 7 inches (2.01 m) high.[99]

Bedroom and carport wing

[edit]The bedroom wing is to the left (north) of the foyer[51][101] and includes three bedrooms and two bathrooms.[10][15][44][d] A narrow hallway or gallery runs northeast from the core.[22][101] The hallway measures about 1.5 feet (0.5 m) wide, barely enough for visitors to pass in single file,[7][54] and its western wall has built-in shelves topped by clerestories.[101] The bedrooms, leading off the hallway, are arranged in a line from north to south. All of the bedrooms have tidewater cypress furniture such as bed frames, cabinets, and shelves, and the same material is used on the walls and ceilings. The southernmost bedroom was used by guests and has a ceiling trapdoor, a private bathroom, and a corner window without any supports at the corner. There is a second bathroom between the central and northernmost bedrooms. The central bedroom has windows facing the bedroom terrace. The northernmost bedroom was the master bedroom and has a triangular chimney with a fireplace, in addition to clerestories on the west wall, larger windows on the eastern wall, and an attic trapdoor.[101] There is also a small water fountain near the master bedroom's windows.[63][65]

Unlike many of Wright's other homes, Kentuck Knob has a basement, which originally contained storage and laundry rooms.[14][101] The hallway's eastern wall leads to a doorway that connects with a stairway to the basement. Shelves were installed in the basement's original storage room in the 1980s, and another storage room in the basement was added at that time.[101] The Hagans had wanted a larger basement, but Wright downsized the basement for practical reasons; since the house was to be constructed on the side of a hill, a full basement would require more excavation than a partial basement.[52]

Next to the bedroom wing is the carport, which extends northwest from the bedrooms, intersecting the bedroom wing at a 120-degree angle.[51] The carport contains three parking spots separated by triangular piers;[98] it has sandstone walls, a pea-gravel pavement, and a ledge on its rear wall.[103] Behind the carport's rear wall is the studio,[95][103] which was originally a pump room but was modified at Bernadette Hagan's request.[19] Cypress doors connect the carport with the studio, which has clerestory windows, in addition to a storage closet on its eastern wall.[103] As built, the house did not contain an attic because Wright disliked that design feature.[54][55] When the house was being built, the Hagans added an attic for storage without telling Wright about it.[55]

Impact

[edit]Reception

[edit]The scholar James D. Van Trump described the house in 1964 as "a document of the mountains and the sky, as well as another profound and valid Wrightian statement of the life of man in nature".[95] A reporter for the St. Petersburg Times called the house "an example of an interior that echoes its exterior surroundings".[69] A writer for The Guardian said that the house demonstrated Wright's tendency to construct non-rectangular rooms and blur the distinction between indoor and outdoor spaces.[104] A Financial Times commentator called Kentuck Knob "a homily to the hexagon",[105] while other writers compared the shape to a ship's prow.[10][73] Wright's longtime archivist Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, who directed the Taliesin West archives, regarded Kentuck Knob as "one of the better executed of Wright's later homes".[7]

After Kentuck Knob opened to the public in 1996, a writer for The Daily American said that the house was "a hospitable, not formidable, estate",[11] and a writer for The Patriot-News said that the house had a timeless aura because of "the forward-looking nature of Wright's design".[53] Another critic, for the Richmond Times-Dispatch, regarded the house as having a "serene setting" and said the design gave the impression that the boundary between indoor and outdoor spaces had been blurred.[84] A Post-Gazette writer, touring the house, described it in 2001 as having "the classiest clutter I've seen recently", despite Wright's aversion to cluttered homes.[106] Ellen Uzelac of The Baltimore Sun wrote that the house has "a quiet quality ... a free-flowing movement and light that changes with the hour",[22] while a writer for the Guelph Mercury said that Kentuck Knob's design exceeded that of a regular residence because it "exudes that unmistakable mania for detail, that sweeping appreciation for nature".[99]

Several commentators have compared Kentuck Knob with Fallingwater. Van Trump said in 1964 that the houses "are completely different in site, outlook and construction".[13] A writer for the Central New Jersey Home News said that the house was smaller in scale and cozier compared to Fallingwater, which was more akin to a palace.[107] The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette wrote in 2001 that, whereas Fallingwater was good for entertaining guests, "Kentuck Knob is a house you can actually imagine yourself cooking breakfast in or folding laundry while you watch TV".[9] Other writers described Kentuck Knob as being cozy and welcoming compared with Fallingwater.[62][55] A New York Times reporter called Kentuck Knob "a gem designed with Wright's trademark ingenuity" despite being "less spectacular" than Fallingwater,[108] while another Times writer said that Kentuck Knob still had many noteworthy design details while being less crowded than Fallingwater.[4] Lord Palumbo personally believed that Fallingwater was "the greater house, but it lacks the human dimension" compared to his own residence.[72]

Media and architectural influence

[edit]Kentuck Knob was designated as a National Historic Landmark in May 2000.[67][109] The same year, the house was detailed in Donald Hoffman's book Frank Lloyd Wright's House on Kentuck Knob,[50][110] which features more than 50 images and diagrams of the house.[56] Additionally, Bernardine Hagan wrote a memoir about the house's development and her experiences living there, writing a draft during mid-1997 while she was in Chautauqua, New York.[111] Hagan's book was published in 2005[58][112] and includes photographs taken throughout the house's history, as well as documents relating to Kentuck Knob, such as copies of the family's correspondence with Wright.[59]

After Kentuck Knob was completed, Wright used local stone and tidewater cypress in some of his later designs.[70] The hexagonal floor grid was also emulated in other Wright-designed structures;[7] for example, in 1953 Wright created an apartment for Edgar Kaufmann Sr. with a hexagonal grid.[113] In addition, the copper roof and stone facade of the Nemacolin Woodlands Resort alludes to the materials used in Kentuck Knob's design.[114]

See also

[edit]- List of National Historic Landmarks in Pennsylvania

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Fayette County, Pennsylvania

- List of Frank Lloyd Wright works

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Some sources cite the site as covering 78 acres (32 ha).[7]

- ^ Another source gives a contradictory figure of 2.3 feet (0.70 m).[50]

- ^ Other sources give figures of 2,500 square feet (230 m2),[7] 3,000 square feet (280 m2),[11] or 3,600 square feet (330 m2).[15]

- ^ Van Trump 1964, p. 23 gives a separate figure of three bedrooms and three bathrooms.

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ "Hagan, Isaac Newton and Bernardine, House". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on October 10, 2012. Retrieved July 2, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j National Park Service 2000, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e f Heyman, Stephen (July 27, 2016). "In Frank Lloyd Wright Country, Architecture and Apple Pie". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ^ a b "Wright home to open to public". Indiana Gazette. March 2, 1996. p. 4. Retrieved April 28, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Carter, Alice T. (May 20, 2001). "Kentuck Knob opens doors to a Wright design". TribLIVE.com. Retrieved April 27, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Sweeney, Jim (August 14, 1997). "Rediscovering Frank Lloyd Wright at Kentuck Knob". The Washington Post. p. 10. ISSN 0190-8286. ProQuest 1458327121.

- ^ Levere, Jane (January 6, 2017). "Frank Lloyd Wright's Kentuck Knob house celebrates its 60th anniversary". The Architect's Newspaper. Retrieved May 1, 2025.

- ^ a b c McKay, Gretchen (June 23, 2001). "Living in the Wright House". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. pp. B1, B2. ISSN 2692-6903. Retrieved April 25, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Beyer 1996, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Best, Jody (October 26, 1996). "Kentuck Knob is a treat for art, architecture fans". The Daily American. p. 17. Retrieved April 25, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d Levere, Jane (January 6, 2017). "Frank Lloyd Wright's Kentuck Knob house celebrates its 60th anniversary". The Architect's Newspaper. Retrieved April 27, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g Van Trump 1964, p. 22.

- ^ a b c d e f "Pennsylvania's other Wright house for sale". The Daily Item. Associated Press. August 8, 1983. p. 23. Retrieved April 27, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Spatter, Sam (January 16, 1983). "Wright-Designed Home for Sale". The Pittsburgh Press. p. H1. Retrieved April 27, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Deitz, Paula (December 28, 1989). "The Keeper of 3 Architectural Icons". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 28, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Forbes, Marilyn (September 3, 2006). "Kentuck Knob marks 50th anniversary". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. ProQuest 382552606.

- ^ a b c National Park Service 2000, pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Lowry, Patricia (June 23, 2001). "Getting a Personal Glimpse of House the Hagans Built". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. pp. B1, B3. ISSN 2692-6903. ProQuest 391236856. Retrieved June 23, 2001 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f Zajac, Frances Borsodi (May 18, 2003). "Art beginning to compete with architecture at Kentuck Knob". Herald-Standard. Retrieved April 27, 2025.

- ^ a b Linn, Virginia (November 2, 2014). "View pieces of Berlin Wall in Fayette County and D.C." Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. ISSN 2692-6903. Retrieved April 27, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Uzelac, Ellen (December 3, 2000). "Dream House". The Baltimore Sun. pp. 1R, 4R, 5R. Retrieved April 30, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Wari, Fitale (June 4, 2017). "Frank Lloyd Wright not the only artist at work here". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. pp. E1, E3. ISSN 2692-6903. Retrieved December 9, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Hoffmann 2000, pp. 18–19.

- ^ "Conservancy nets 200 acres for Ohiopyle". Latrobe Bulletin. September 23, 2008. pp. A5. Retrieved May 1, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Stabert, Lee (February 27, 2017). "On the Way to...Frank Lloyd Wright's Fallingwater". Keystone Edge. Retrieved December 7, 2024.

- ^ a b "An architectural masterpiece". Centre Daily Times. May 26, 2014. pp. QF13, QF15. Retrieved December 9, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Western Pa. offering Wright 'trinity' tour". Lancaster New Era. Associated Press. September 3, 2007. p. 10. Retrieved December 8, 2024 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Dvorak, Amy (May 20, 2019). "Frank Lloyd Wright's Mäntylä House Opens to Overnight Guests at Polymath Park". Dwell. Retrieved December 8, 2024.

- ^ a b "County Has Two Homes by Wright". Evening Standard. April 9, 1959. pp. 1, 6. Retrieved April 28, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Ellis, Franklin (1882). History of Fayette County Pennsylvania. L.H. Everts & Company. p. 775. Retrieved April 25, 2025.

- ^ Netting, M. Graham; Western Pennsylvania Conservancy (1982). 50 years of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy : the early years. Pittsburgh, Pa.: Western Pennsylvania Conservancy. pp. 132, 136. OCLC 9280879.

- ^ Lindeman, Teresa F. (April 10, 2002). "Having a Moment After Serious Market Research, Hagan Readies New Line of Ice Creams for Rollout". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. C1. ISSN 2692-6903. ProQuest 391223824.

- ^ a b c National Park Service 2000, pp. 11–12.

- ^ National Park Service 2000, p. 11.

- ^ a b c Hoffmann 2000, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d e f Beyer 1996, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Pickering, Silas (March 30, 1957). "Designed for Living". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. 19. ISSN 2692-6903. Retrieved April 26, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h National Park Service 2000, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d Fischer, David (August 11, 2002). "Workers take on masterpiece". Troy Daily News. pp. C1, C3. Retrieved May 1, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Hoffmann 2000, p. 15.

- ^ Beyer 1996, pp. 3–4.

- ^ a b Hoffmann 2000, pp. 17–18.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Uricchio, Marylynn (January 9, 2020). "Kentuck Knob". Pittsburgh Quarterly. Retrieved May 1, 2025.

- ^ a b c d Beyer 1996, p. 4.

- ^ a b c Hoffmann 2000, p. 18.

- ^ National Park Service 2000, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Hoffmann 2000, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Dengler, Ashley (Spring 2010). "Kentuck Knob: A True Masterpiece". Pennsylvania Center for the Book. Retrieved April 28, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "History of Kentuck Knob Comes Alive in New Book". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. July 1, 2000. p. B8. ISSN 2692-6903. ProQuest 391989976.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Storrer, William Allin (1993). The Frank Lloyd Wright Companion. University of Chicago Press. p. 405. ISBN 978-0-226-77624-8. (S.377)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j National Park Service 2000, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Sweeney, Jim (May 10, 1998). "Kentuck Knob, an architectural wonder". The Patriot-News. pp. J4, J5. Retrieved April 28, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d Anderson, Wayne; Anderson, Carla (September 30, 2007). "Wright's Kentuck Knob reflects whimsy". Columbia Daily Tribune. p. 42. Retrieved May 1, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d Decker, Cindy (May 4, 2017). "Falling for Frank Lloyd Wright in Pennsylvania's Laurel Highlands". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 1, 2025.

- ^ a b Bradley, Mary O. (July 9, 2000). "Bookings: Historian looks at Wright's Kentuck". The Patriot-News. pp. E3, E4. Retrieved April 30, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Zuchowski, Dave (April 11, 1999). "Kentuck Knob stonework is a legacy to their skill". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. pp. G3, G6. ISSN 2692-6903. Retrieved April 28, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f Nephin, Dan (June 13, 2005). "Book showcases well-known architect". Republican and Herald. p. 2. Retrieved April 30, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d Lowry, Patricia (June 4, 2005). "Book of Bernardine Hagan's recollections of Kentuck Knob is finally published". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. ISSN 2692-6903. Retrieved April 25, 2025.

- ^ McLaughlin, Katherine (July 17, 2024). "Working With Frank Lloyd Wright: The Architect's Last Living Client Shares His Experience With the Visionary". Architectural Digest. Retrieved April 28, 2025.

- ^ a b Beyer 1996, pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b c d McDevitt Rubin, Marilyn (October 12, 1997). "Hobnobbing at Kentuck Knob". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. G14. ISSN 2692-6903. ProQuest 391624755. Retrieved April 28, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Sheridan, Patricia (June 4, 2017). "Falling Rock hotel is a chip off the old Wright". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. ISSN 2692-6903. Retrieved May 1, 2025.

- ^ "The story behind Frank Lloyd Wright's Kentuck Knob". CBS Pittsburgh. June 5, 2024. Retrieved May 1, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f National Park Service 2000, p. 14.

- ^ a b c "County Has Two Homes by Wright". The Morning Herald. April 10, 1959. p. 6. Retrieved April 26, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Tourists discover Wright's other house". The Daily News. Associated Press. May 29, 2000. p. 4. Retrieved April 30, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Tormay, B. J. (August 13, 1963). "Hagan House Outstanding House Tour Attraction". Evening Standard. p. 12. Retrieved May 1, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "They endure and grow in value". Tampa Bay Times. January 16, 1983. p. 93. Retrieved April 28, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i John-Hall, Annette (August 17, 1997). "The curator and his art". The Philadelphia Inquirer. pp. R1, R6, R7. Retrieved April 28, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hazell, Naedine Joy (July 22, 2001). "The Angle on a Country Home Wright's Kentuck Knob Broke the Rules About Square Houses". The Hartford Courant. p. F1. ISSN 1047-4153. ProQuest 256500588.

- ^ a b Owens, Mitchell (July 25, 1996). "Currents;A Wright House, Not a Shrine". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 28, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f Miller, Donald (May 4, 1996). "All the Wright Moves". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. pp. D1, D2. ISSN 2692-6903. Retrieved April 27, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Bertrand, Amy (April 30, 2025). "Love Frank Lloyd Wright? Visit Pennsylvania". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Retrieved May 1, 2025.

- ^ a b "Around the Nation; Fire Damages a House Designed by Wright". The New York Times. Associated Press. May 28, 1986. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 27, 2025.

- ^ a b c "Cause sought in fire at landmark Fayette house". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. May 28, 1986. p. 4. ISSN 2692-6903. Retrieved April 28, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e Miller, Donald (March 1, 1996). "Kentuck Knob may soon gain fame". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. A1. ISSN 2692-6903. ProQuest 391839079.

- ^ a b c d e f g Coates, Claudia (May 12, 1996). "Frank Lloyd Wright's Kentuck Knob opened to public". The Patriot-News. Associated Press. pp. F1, F6. Retrieved April 25, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b National Park Service 2000, p. 8.

- ^ a b c Lowry, Patricia (May 16, 2000). "City architect will design Kentuck Knob visitors' center". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. 37. ISSN 2692-6903. Retrieved April 25, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d Brown, Patricia Leigh (December 19, 1996). "Old Houses, Just Gotta Have 'Em". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 28, 2025.

- ^ "'Red Army' installed at Kentuck Knob". The Daily American. August 30, 1997. p. 109. Retrieved April 28, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Lowry, Patricia (June 30, 1999). "Bilbao Guggenheim Architect May Design Kentuck Knob Visitors Center". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. E1. ISSN 2692-6903. ProQuest 391454373.

- ^ a b c d Calos, Katherine (March 22, 1998). "Wrighting a wrong". Richmond Times-Dispatch. pp. J1, J2. Retrieved April 28, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Kentuck Knob Opens to Sunrise". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. July 10, 1999. p. D6. ISSN 2692-6903. ProQuest 391476226.

- ^ "Visitor Center at Kentuck Knob". Latrobe Bulletin. Associated Press. May 17, 2000. p. 12. Retrieved April 25, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Kentuck Knob Ceremony Nov. 6". Latrobe Bulletin. October 30, 2000. p. 5. Retrieved April 25, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Kentuck Knob Visitor Center". The Progress Fund. January 4, 2023. Retrieved April 30, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g National Park Service 2000, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b c d e f National Park Service 2000, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Bleiberg, Larry (June 5, 2015). "10 great Frank Lloyd Wright home tours". USA Today. Retrieved April 27, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j National Park Service 2000, p. 5.

- ^ a b Mallette, Catherine (May 15, 2016). "Natural connection". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. pp. D1, D8, D9. Retrieved May 1, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Zak, Victor (January 5, 1997). "The Wright train in Pennsylvania". The Central New Jersey Home News. p. 48. Retrieved April 28, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g Van Trump 1964, p. 23.

- ^ National Park Service 2000, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Van Trump 1964, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n National Park Service 2000, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Storring, Kathryn (August 7, 2004). "Fallingwater; Frank Lloyd Wright's creation blends seamlessly with nature". The Guelph Mercury. p. H14. ProQuest 355669879.

- ^ "Despite Need for Restoration, Innovations of Wright House Evident at Oberlin". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. January 22, 2000. p. D2. ISSN 2692-6903. ProQuest 391382375.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k National Park Service 2000, p. 7.

- ^ Buchanan, Katy (December 10, 2006). "Hobnobbing at Kentuck Knob". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. F2. ISSN 2692-6903. ProQuest 390650970. Retrieved May 1, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c National Park Service 2000, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Blaney, Paul (December 17, 2011). "Travel: Architecture: Do the Wright thing: Three Frank Lloyd Wright houses can be visited on a day trip from Pittsburgh. Paul Blaney even gets to spend a couple of nights in one". The Guardian. p. 9. ProQuest 911736258.

- ^ Manson, Katrina (February 17, 2021). "My night with Frank Lloyd Wright". Financial Times. p. 6. ProQuest 2503358393. Retrieved May 1, 2025.

- ^ McDevitt Rubin, Marilyn (June 10, 2001). "On the inside and out, Fallingwater has the Wright attitude". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. 86. ISSN 2692-6903. Retrieved April 30, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Zak, Victor (January 5, 1997). "The Wright train in Pennsylvania". The Central New Jersey Home News. p. 48. Retrieved May 1, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Schneider, Bethany (August 25, 2006). "Pennsylvania, the Land of Fallingwater and Flight 93". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 1, 2025.

- ^ "Home draws more visitors". York Daily Record. May 29, 2000. p. 1. Retrieved April 30, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Dream House". The Baltimore Sun. December 3, 2000. Retrieved April 28, 2025.

- ^ Lowry, Patricia (July 17, 2002). "Publishing spouses turn local history into page-turners". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. 43. ISSN 2692-6903. Retrieved April 30, 2025 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Kentuck Knob; Frank Lloyd Wright's house for I.N. and Bernardine Hagan". Reference and Research Book News. Vol. 20, no. 3. August 2005. ProQuest 199683390.

- ^ Lowry, Patricia (March 12, 1999). "Model Apartment Shows Wright Stuff". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. D1. ISSN 2692-6903. ProQuest 391512806.

- ^ Zuchowski, Dave (August 8, 2004). "Resort Luxury Goes to New Level With Falling Rock Boutique Hotel". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. W1. ISSN 2692-6903. ProQuest 390863759.

Sources

[edit]- Beyer, Sarah (October 1996). "From Cows to Cantilevers: Kentuck Knob and the Kaufmanns". Friends of Fallingwater Newsletter. No. 15. pp. 1–6.

- Hagan, Bernardine (2005). Kentuck Knob: Frank Lloyd Wright's House for I.N. and Bernardine Hagan. Pittsburgh, Pa: The Local History Company. ISBN 0-9711835-5-4.

- Historic Structures Report: I.N. And Bernardine Hagan House (Report). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. January 2000.

- Hoffmann, Donald (2000). Frank Lloyd Wright's House on Kentuck Knob. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-8229-4119-4.

- Van Trump, James (April 1964). "Caught in a Hawk's Eye: the House of I.N. Hagan at Kentuck Knob". Charette. Vol. 44, no. 4. pp. 22–23.

Français

Français Italiano

Italiano